Thursday Nights at Toads…

On November 15, 2007, I attended a show from the “Hip-Hop Live” tour, featuring an older generation of rappers including Brother Ali, Ghostface Killah, Rakim, as well as the hip-hop band, the Rhythm Roots All-Stars. From one song to the next, the audience held onto every word as the rapper’s flow wove in and out of the rhythm of the band’s groove. The virtuosity of the rappers, particularly their ability to respond to the changing groove, revealed how the excitement of this music thrives on rhythmic tension the groove, a metric temporal phenomenon featuring multiple layers interlocked with varying syncopated rhythmic ostinatos, and the flow, or the rhythmic delivery of the rapper’s lyrics. Given the dynamic relationship between the groove and flow, any hip-hop analyses must address the question of how these two phenomena are rhythmically related. Throwback Tunes: DJ Play My Favorite Song will begin with an overview of hip-hop, tracing the rise of the DJ and the subsequent rise of the rapper. I will then dive into an analysis of Jay-Z’s “Money, Cash, Hoes,” featuring DMX.

Rhythm and Rhyme

The history of hip-hop begins during the disco era, when DJs began to transform popular dance tracks by manipulating recording equipment. DJs focused on the “break,” or that moment during a song when the rhythm section engaged dancers through an extended solo section, soon developing the following techniques to add rhythmic variety from one track to the next:

(1) Cutting: switching in the middle of one track to another one

(2) Mixing: overlaying sounds from one record with/onto another

(3) Scratching: physically moving the record needle back and forth during a musical phrase, producing an additional percussive sound independent of the current track

In the early days of hip-hop, the DJ was the central figure, judged by fans for how well s/he experimented with popular dance tracks. New technologies made possible for the spread of hip-hop out of the New York City area, and by 1979, the release and popularity of such singles as “Rapper’s Delight” and “King Tim III” signaled a shift towards the rapper as the main interpreter of hip-hop’s authentic sound. While standard DJ techniques account for the disjunctive, fragmented rhythms which continue to remain a hallmark feature of the hip-hop aesthetic, the rhythmic delivery and intonation of the rapper’s style have since become a defining characteristic of rhythm in hip-hop. The degree to which the rapper creates rhythmic tension with the groove has become a key factor in differentiating the styles of today’s rappers. One illustrative example comes from Jay-Z’s “Money, Cash, Hoes,” the third single released from his album Vol. 2, Hard Knock Life. On this track, Jay-Z raps for the first of three verses, and DMX takes over on the third.

Money, Cash, Hoes: Groove

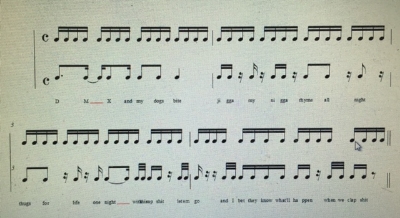

Looking at the hi-hat layer of the groove, the smallest division of the beat occurs at the sixteenth-note level. The absence of a beat at the quarter-note level in the four-measure bass ostinato gives room for unequal sixteenth-note groupings. In the bass, the first attack after the downbeat occurs on the fourth sixteenth-note, thus grouping the first three sixteenth-notes together. The following three sixteenth-notes are grouped together, when the synthesizer (high) sounds on the seventh sixteenth-note. Given the bass eighth-notes in the first and third measures, the remainder of the sixteenth-note beats resumes a duple grouping. While the initial triple grouping of the sixteenth-notes and the off-beat attacks in the synthesizer (high) layers suggest that the off-beats may be interpreted as metrically strong, the quarter-notes in the second measure of the bass layer force a hearing of the attacks in the synthesizer (high) layer as off-beats.

J-A-Y

A comparison between Jay-Z and DMX illustrates how these two rappers interpret the meter of the groove in this track. The first four lines of Jay-Z’s opening verse demonstrates how Jay-Z’s approach to flow is flexible yet consistent with meter of the background groove:

J-A-Y, I flow sick

Fuck all y’all haters blow dick

I spits the games for those that throw bricks

Money, cash, hoes, money cash chicks what

Jay-Z spells out the first three letters of his name in such a way that confirms the opening 3+3 metric grouping of the sixteenth-note pulse. Repeating this rhythm in the second measure, “all” and “y’all” similarly land on the fourth and seventh sixteenth-notes of the measure. In the third measure, however, the 3+3 grouping shifts by a sixteenth-note. The concrete words in this phrase, “spits,” “games,” “those,” “throw,” and “bricks,” are each sustained for an eighth-note, thus conferring accentual weight. At the beginning of the fourth measure, the first beat appears identical to that of the previous measure. However, given the accent on the word “cash” Jay-Z returns to the 3+3+2 sixteenth-note grouping that dominated the beginnings of the first two measures.

D-M-X

D-M-X and my dogs bite

Jigga my nigga rhyme all night

Thugs for life one night with this rap shit

Let em go and I bet they know what’ll happen

When we clap shit

In the first measure, DMX spells out his name rhythmically identical to Jay-Z’s opening verse. However, in the second, his intonation forces a regrouping of a pulse that conflicts with the groove. DMX maintains the same volume level throughout these first four measures, thus overriding the flow of the syntax, and forcing the listener to interpret every attack as metrically strong. For example, in measure two, the first two quarter-note beats suggest a 3+2+3 sixteenth-note grouping, whereas the comparable beats in the following measure suggest a 2+3+3.

Rhythmic analysis of hip-hop must address the rhythmic interplay between the groove and the flow. The groove, a highly repetitive, syncopated framework that engages with irregular phrase groupings, creates a rich, rhythmic palate for the vocal delivery. The brief glance at “Money, Cash, Hoes” illustrates how syntax and rhyme dictate Jay-Z’s approach to beat-pulse groupings, whereas DMX relies more heavily on intonation to challenge the logic of the syntax, thus creating another layer of rhythmic tension against the meter of the groove.

As I looked around at the diverse audience at “Hip-Hop Live,” listeners and dancers were collectively locked into the repetitive, syncopated rhythms of the groove. But when the rappers took center stage, and lyrics were spontaneously spun out, the rhythmic energy in the room became instantaneously electrifying, and the crowd went wild.