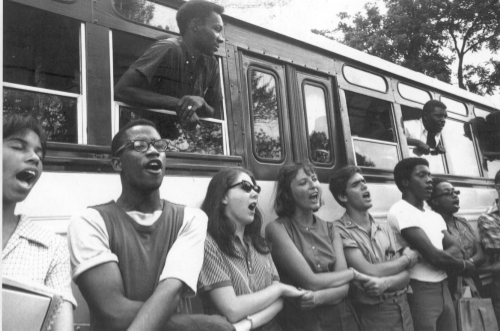

Since I was a little girl, I’ve been singing “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” and “We Shall Overcome” at family and community functions, and yet, their significance was something I could only begin to understand as an adult. While I reflect proudly on the legacy of those who paved the way for major civil rights legislation to be passed, I can’t help but notice how much work still needs to be done. As phrases like “I Can’t Breathe” and “Hands Up Don’t Shoot” permeate and puncture the fabric of American society, today’s soundtrack is decidedly harsh and unforgiving. This essay is about Optimism and Disillusionment in the music of modern civil rights movements.

“With a song, there was nothing they could to block what we were saying … Singing is different than talking, because no matter what they do, they would have to kill me to stop me from singing … Sometimes they would plead and say, ‘Please stop singing.’ And you would just know that your word is being heard”

In 1945, during a labor strike of the Negro Food and Tobacco Union Workers, Zilphia Horton, then music director at the Highlander Folk Center, learned the hymn-turned-protest song as “I’ll Overcome Someday.” As the story is told, she then taught it to Pete Seeger, who replaced “I” with “We.” It was this revised version of the song that Seeger shared with the Center’s new music director, Guy Carawan, who introduced it to student civil rights activists in the 1950s. At the founding convention of the Student for Non-Violence Coordinating Committee in 1960, members joined together in singing, “We Shall Overcome,” and it was at that moment that the freedom song became officially linked with the civil rights struggle. With its simple, yet poignant refrain, and a melody that slowly rises over the third statement of the title phrase, the song quickly became a symbol of hope for a new society, governed by its founding principle of equality for all.

"Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)"

Late in the summer of 1965, a riot broke out in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. 14,000 National Guardsmen descended upon the scene, and over the course of several days, 34 individuals were killed, with the cost in damage coming to about $35 million. One year later, protests and violence erupted in the West Side of Chicago, followed by riots in major cities across the country. This was low-level warfare raging on American soil, and in was response, a new era of the movement was beginning to take shape. In the words of Stokley Carmichael, the time had come for “no more long prayers, no more Freedom songs, no more dreams.” It was time to “go for power.”

When Bobby Seale and Huey Newton established the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, they called for freedom and power, addressing the most basic human instinct, survival. Black bodies were on the brink of extinction, and it is this primal fear that provides the fuel for the #BlackLivesMatter movement. While the rallying cry for today’s movement comes in the form of a hashtag, we can identify a powerfully-sustained response from the creative community, including D’Angelo’s Black Messiah, Rhiannon Giddens’s “Cry No More,” and Janelle Monae’s “Hell You Talmbout.”

However, the most in-your-face discourse comes from Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly. Complex, twisted, and unrelenting from the first track to the last, distrust and depression go hand-in-hand, as the music swerves in and out of its own frenzied funk. In an imagined conversation between Lamar and 2Pac, the groove grinds to a halt, becoming a distant memory as Lamar reminds us, "In my opinion, only hope that we kinda have left is music and vibrations, lotta people don't understand how important it is."

Today, many of us will come together singing “We Shall Overcome Someday” with a sinking feeling that someday isn’t coming soon enough. While 2015 will be remembered as a pivotal year in Black radical politics, “This ain’t nothin’ new,” my mom once told me. “We’ve been fighting for this for years.”

Playlist

Sing for Freedom: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement Through Its Songs

Curtis (Curtis Mayfield)

What’s Goin’ On (Marvin Gaye)

To Pimp a Butterfly (Kendrick Lamar)